The world of sharks is enormous; there are around 530 known species swimming in the earth’s oceans and lots of them do so around New Zealand – a fact that has kept me from swimming far out but I’d happily assist a marine scientist with applied shark research on Stewart Island/Rakiura. I was honoured to serve NZ’s oldest university, keen to see some not-in-a-tank, bad-ass sharks, and also, really looking forward to brag with “We do shark research” in the local pub.

Bluff & the notorious Foveaux Strait: most likely place for a Sharknado to occur

Leaving Otago down south, I hitchhiked near Invercargill, and Adam, on his way home from work stopped for me. We drove down the Bluff Highway and came across a giant dark curtain above the horizon.

“That is Rakiura”, said Adam.

“No way!”

“Yes, it is, man. It’s huge!”

The reason for my astonishment of seeing Stewart Island from mainland were those 30km of water passage between Bluff and Stewart Island, the Foveaux Straight. The strait is famous for its unpredictable depth and moodiness since the waters are driven by the Roaring Forties, strong westerlies winds of latitude 46, that are enhanced since there is no real land between here and Argentina.

The Foveaux Straight is so hazardous because of its varying depths (as low as 25 metres). No problem for the ferry. A tanker, however, better has deep sea sonar on board. The real danger though comes from the currents and swells that the westerlies cause. Waters to the south of the Te Waewae Bay and and west of Stewart Island reach depths of 300 to 600 meters. These deep water bodys can take up speed rapidly when flushing through the shallow waters of the Foveaux Straight.

Bluff is a little settlement on the southern tip of the South Island, “the first city of New Zealand”, if you start your journey from Antarctica. It is famous for Bluff Oysters, The Oyster Festival and place called Stirling Point. Adam mentioned New Zealand’s only aluminium smelter to be down here at Tiwai Point – importing the raw material (Bauxite) from Australia and exporting aluminium goods mainly to Japan.

Among the supplies for Stewart Island was a bottle of whiskey for Rob and I, because rumours say that drinking is a standard procedure for men of the sea. I explored a bit of what is known as Bluff Hill, and took a little detour through spiky gorse. Geologically, Bluff Hill is closely related to Stewart Island’s northern half – igneous rock (cooled down magma) that formed plutonic granite, originating from supercontinent Gondwana.

When Captain Cook circumnavigated New Zealand for the first time in 1770, the crew must have witnessed the power of the Roaring Forties. Cook’s first map did not even include the Foveaux Straight, and Stewart Island/Rakiura was depicted to be a large peninsula. He was writing about “unfavourable” weather conditions that kept the Endeavour off shallow coast territories. Or Cook and crew had simply too much rum…

The straight once was a coastal plain – before the last glaciation ended some 10,000 years ago. What remained are its highest points like Ruapuke or the Titi Islands that we passed on this smooth ferry ride. The ferry would not consider a transfer at windspeeds over 50 knots (92km/h), which is a piece of cake for the Foveaux Straight.

Preparation, Patience, and the Paterson Inlet

Otago’s Marine Science is probably one of the university’s most famous departments. Rob awaited me in Halfmoon Bay and we went straight for a short drive through town. That wouldn’t take long since Oban counts about 400 permanent residents and only 28 kilometres of solid road.

Rob is a marine science master student and sharks are sort of his thing; he is experienced and participated in Great White research in South Africa before. Here in the Paterson Inlet, Stewart Island/Rakiura’s biggest sea arm, he is aiming to count and investigate the inlet’s seven-gilled shark population.

We drove back to the Rakiura Marine Field Station, and talked about sharks over whiskey for the rest of the night. Rob made sure that we were good to go for the next morning: charged batteries and empty SD cards for the GoPros, fuel, bait and a GPS. The whiskey made me sleepy, and that was great because we planned to be on the water by no later than 7:30 am.

If you are working on a data set like Rob is, it is important to minimize the factors that could weaken or invalidate your hypothesis. That means that we’d drop the GoPros at different spots, times (morning vs. afternoon), and seasons. Shark research, well any kind of research, is time-consuming but new data can teach us more about the only little investigated seven-gilled sharks. Would I finally get to see a shark outside an aquarium and the freezer?

Every day, Rob would loosen Moki, our little research vessel, and pick me up from the dock at Golden Bay Wharf near Iona Island. Within 50 meters away from the wharf, Rob would use the radio – a necessity on sea and something like an unwritten rule on Stewart Island/Rakiura: always tell someone where you are planning to go.

“Bluff Fishermen Radio, Bluff Fishermen Radio. This is Moki, over”, Rob spoke into the radio, gallantly but distinctively.

Answering was a lady called Mari, a retired volunteer based in Bluff who operated the radio from the mainland, communicating with local boats and updating everyone about the weather forecast. Rob shared our plans with her; he wouldn’t exactly flirt with Mari but always be kind. She was a busy lady, so Rob would sometimes flick her a message.

“Would you please not text and drive?”

Currents near the inlet’s entry could easily sweep you out. The water is a little bit warmer than ice and besides, its Great White Carcharodon carcharias territory. We knew we’d be safe once Mari returned.

“Good as gold”, was her catch phrase.

The sun melted our morning frost and there was almost no wind. We hit out westwards to Sawdust Bay, a water arm named by early saw millers. According to Rob, the dark and almost muddy water of Sawdust Bay is a hotspot for sevengills. The latest specimen Rob witnessed spy-hopping was a 2.3 metres-long female. We saw shags, gulls, and a little blue penguin before we even arrived.

Rob threw the anchor out and instructed me to take notes. Time, wind speed, cloud cover, and coordinates. In addition, we’d take the surface temperature (12°C that day) and use a refractometer, a device that uses Snell’s Law and the refractive index to measure water salinity. It was 33 ppt (parts per thousand), so 3.3% salt, 96.7% water. The average salinity of sea water is about 35 ppt. This slightly lower value is caused by some of Stewart Island’s many freshwater streams some of which flow into the Paterson Inlet. Among them is the island’s biggest stream, the Freshwater River.

Time to drop the cameras that we needed for stereophotogrammetry. Photogrammetry is the process when measurements are taken from a set of photographs to determine three-dimensional coordinates (“positions of surface points”) of an object. So if I’d take a short video of a Stewart Island shag flying by – using a photogrammetry software – I could make a close estimate of how far the bird was away from me or above the water.

The camera cases are fixed onto a metallic bow made by an engineering student just for the purpose of Rob’s research. Two GoPros are placed around the arch’s centre. Their fields of view overlap, the coordinates are estimated from two different positions, and Rob is able to cover more ground. The bait box is filled with yummy barracuda and blue cod, a Stewart Island delicacy.

The rest was a waiting game – more time to think of creative names for our research subjects, to list all the silly shark movies we knew and of course, to learn more about New Zealand’s seven-gilled sharks.

“What’s your favourite?”

“Man, the mako. A top-predator and the fastest of them all. It’s shaped like a bullet.”

Sevengill Science

As predicted, we were fortunate to see a sevengill in Sawdust Bay. Rob spotted a fin in the far, and mentioned that we’d be super lucky actually seeing one breaching the surface. We watched the water carefully.

“Bananas and eggs bring bad luck on a boat.”

“Oh yeah and sharks, for some reason, like to play with yellow things.”

He said that so smoothly, almost out of nowhere, while I had just downed the last piece of my banana, and wrapped in my yellow raincoat, looked like a giant one myself.

“Bite me, Rob.”

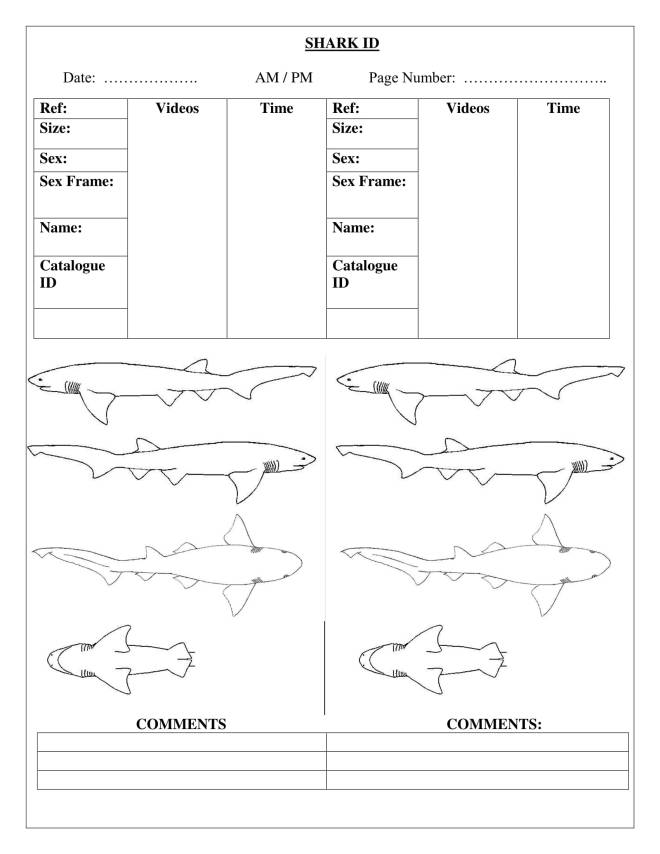

Rob is an expert in his field and knows his broadnosed sevengills Notorynchus cepedianus – he has gone through lots of footage for several seasons and is now able to distinguish a recorded shark from another by recognizing the unique dotted pattern on the back of the fish. Sharkira, Sharpedo, Fintastic – Rob has been through a lot of strange names – but the specimen we had unknowingly caught on camera seemed to be a visitor. Her name would be Wynona.

Wynona was a 2.2 metres adult female, assumed to be 11 to 16 years of age. The biggest sevengill Rob has seen so far was 40 cm longer and a bit older. Probably a female because in the world of sharks, the Wynonas are usually larger than the Williams. Male sharks can be differentiated by calcium claspers (a penis really) near the pelvic fin. Researchers estimate sevengills to become between 30 to 50 years old. The longest living vertebrate is the Greenland shark Somniosus microcephalus and believed to live around 400 years (#radiocarbondating).

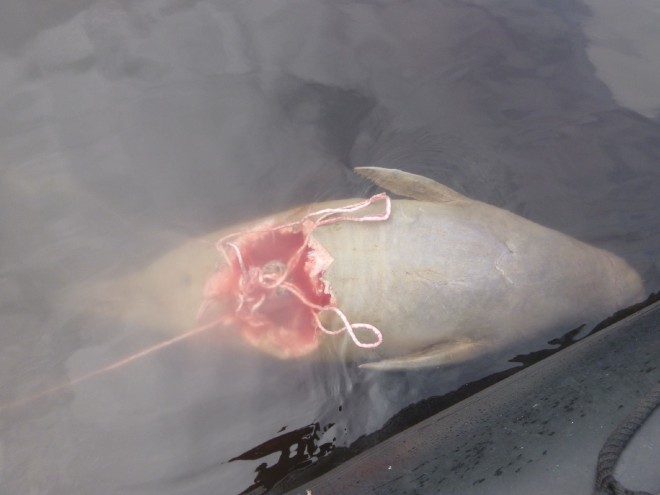

Wynona is a mesopredator and primarily scavenging, she feeds on smaller sharks and other fish – but represents a potential meal for Great Whites and mako. Like the majority of sharks she is ovoviviparous (like Great Whites) – meaning Wynona lays her eggs and hatches them both inside the body where the pubs feed on egg yolk inside the shell (or each other). Vivipars like blue sharks in Otago waters or hammerheads in the Bay of Plenty are similar but feed their pubs via the placenta. Oviparous (egg-laying) sharks include the common cat shark, carpet shark and more.

The “mermaid’s purse” is a common term for chondrichthyes – the capsule or pouch surrounding a shark’s fertilized eggs.

Almost all species have five gills. But nature wouldn’t be nature if all sharks were equal. Among those outliers are the common broadnosed, the sharpnosed Heptranchias perlo sevengill and the sixgill sawshark Pliotrema warreni. It is assumed that these sharks are related to ancient shark fossils of the Jurassic period and to have survived the Permian extinction (When life nearly died: the greatest mass extinction of all time, Benton M J, 2005). And that just adds another question to Rob’s research list: How the hell did they survive?

“Do you believe that the megalodon is still out there, Rob?”

“No?!”

Sevengills have a reputation of being “aggressive” towards swimmers and divers, especially in shallow waters but remember, it is their territory, not ours. They have been recorded to hunt in packs and who wonders, it is New Zealand’s most common inshore shark and has populations around the world. Compared to bony fish, sharks, skates, and rays have a skeleton made up of cartilage allowing them higher flexibility and mobility. Great features for a predator.

“They are curious animals, extremely agile and save their energy for surprising, rapid attacks.”

Over 100 shark species have been sighted in New Zealand waters – only a handful is protected like the whale shark, the basking shark and the Great White excluding the mighty sevengills that are positioned ‘only’ in the middle of the food chain (but actually play an important role in coastal ecosystems). So it happens that sevengills often end as by-catch, and rig sharks Mustelus lenticulatus as the fish of the fish’n’chips in the local pub.

“Threats are by-catch and recreational fishing since they have no conservation status, yet.”

The Perspective

The absence of a conservation status may help Rob to underline the importance of his research, and he is willing to continue with a PhD. “The upcoming marine science students seem very interested – and might take over my work.” But only under one condition: Rob gets to lead as he plans to expand his research to the South Island and especially Fiordland. He aims to finish his master thesis after another season on the flat Stewart Island/Rakiura in January.

“I don’t like mountains.”

Rob’s list of questions to answer is long. Are sevengills travellers like the Great White? When and how do they breed exactly? And how did they survive the mass extinction?

Now I can understand Rob’s fascination for sharks – they are ridiculously diverse: cold or warm-blooded, deep sea species or shallow water hunters, food for other predators or extremely long-living. They are intimidating but mythical, and we only know so little about them. I unfortunately (or fortunately?) did not get to see one, only on camera but I gained a friend, learned so much about sharks, and also what’s it like to be a marine scientist.

Sharks near Stewart Island/Rakiura include rig sharks, sevengills, porbeagle, blue sharks, catsharks, carpet sharks, roughskates, great whites, mako and many more.

“If you ever witness a beach whaling, be careful in the water. Great whites follow the smell of whales for fucking ages, and sevengills, too.” – Rob. 🙂